I’m picking blueberries with the Syrians.

It is hot, windless. We kneel in scratchy grass in the cricketing mid-morning. We assured the women that no men would be in the field, but both wear long skirts and black capes, and keep their heads covered with hijabs.

My friend Patricia is farther up the hill with Azzah, the older of the women, and I’m down lower with the younger one, Muminah, who arrived in New Brunswick only seven days ago. Muminah and her husband are Bedouins. He was a shepherd before war came to their village. In the car, lurching along the dirt road coming up to the field, I sat beside Muminah, wondering what this Canadian hill farm looked like to her. I tried to imagine her Syrian life—the bed in which she woke, the doorway in which she stood hearing roosters and sparrows, the smells of spice, manure, and dust. She gazed back at me, her green eyes proud, sardonic. “Animals ?” I said, stroking an imaginary neck, baaing like a sheep. She laughed, nodded, and baaed back. The two women spoke rapidly to one another in Arabic ; and the car tires scrabbled on loose rocks as the lane wound up into the poor-soiled field where apple trees spread their branches over wispy grasses, goldenrod, and the sprawling, leathery-leaved blueberry bushes.

Muminah picks with a country woman’s practised motions, although neither she nor Azzah have ever eaten blueberries nor know how to prepare them. As her hands move, she begins to sing the way one sings to a baby rocked in one’s arms, a body’s response, like birdsong at dawn ; the melody rises, quavers, and then tails away, the final note lower than the first. The song is clear and strange, like a bird blown off-course ; it evokes thirst, the complaint of camels, a merciless sky. Beyond, at the edge of the spruce trees, is a log cabin. I note this conjunction—the log cabin, the singing Syrian woman—and I remember how, when we helped our friends build that cabin forty-five years ago, we, too, had become immigrants.

I think of how attachment to place is a long process.

We didn’t have to flee from the United States, when we came to Canada, although many of our friends did—draft-dodgers or army deserters. My husband had evaded the draft legitimately, his file shelved in a non-active category. Nonetheless, we moved to New Brunswick, the province in which my grandfather had been born, hoping to find an Edenic world, a balance of farm and wilderness ; and this is what I saw as we drove up the Saint John River valley in the spring of 1970. There were cans of cream on wooden stands ; wind-flaunted laundry ; grazing cows. Spreading over the hills was a patchwork of gold, black, green —dandelions, ploughed soil, new grass—stitched by the pink and white blossoms of cherry trees.

I didn’t realize, then, that I would eventually let the sediment of memory clear from my mind in order to see the place as it was rather than the place I wanted it to be ; that I would cease making comparisons to what I had left behind ; that I would accept the shifting shape of my dream ; that I would be transformed by humility, respect, and the shock of truth. Wind, snow, the yield of soil and the shortness of summer—these things constituted specificity of place with its ensuant human culture. On that drive up the Saint John River valley, I had not yet taken into account that although I spoke one of Canada’s languages, I did not know the subtle manifestations of this particular configuration of planet and people ; I did not know how hard-won this knowledge would be or the extent to which its acquisition would shift me from being an outsider to being a member of a community.

Muminah calls to Azzah. Then she scrambles to her feet and walks back down the hill. She sits in the car, its door half-opened. “She needs to get out of the sun,” Patricia calls, but I wonder if it is taxing to pick berries whose taste is alien, that have no place in any Syrian recipe. Or if, perhaps, she can’t shed the fear that bombers will suddenly appear over the trees. Maybe she needs to close her eyes and dream herself back to her pre-war village. I wonder how long it will take before her pride transfers itself to a new land. I want to tell her how an immigrant is eternally homesick, but that this abates once you can call two places home ; how she will sense New Brunswick creeping into her voice and her heart ; and that, finally, the place where her children are born will be the place she will want to stay.

The berries are lush, a single bunch filling my palm like a sprig of tiny grapes—so many, I think, like all my mistakes. I could tell Muminah how, making the cabin, we felled spruce trees in the fall and let them lie all winter. The following summer, the fibrous bark had dried tight to the cambium ; our drawshaves left scars of ignorance on the golden sapwood. I could tell her how, where I came from, tea bags had little strings ; here, I used to drop one stringless bag in each cup until I learned to interpret our visitors’ amused, furtive silence. Or how we learned never to offer money for a favour, since neighbours store up good-will for their own times of need. I could advise her that to become a New Brunswicker is to grow into days and nights and years of being small in a rough land, a land of blizzards, blackflies, rhubarb, wind-tattered clear-cuts, chainsaws and snowmobiles, gravel roads, moose tracks furrowing thigh-deep snow, the calligraphy of wind, the sighting of weasels, fiddle tunes, foxes, stars over the Orange Hall, rain on Remembrance Day, visiting royals : and a place of many voices—so many rhythms, so many accents—from a multitude of people ; those who were here first, all those who came later.

…

I found out that the sun-warmed berries went into the trash because the Syrian women’s husbands would not eat them.

…

The next summer, Patricia brings the women again. They stop at my house to ask if they can go up to the field and pick blueberries. Muminah is pregnant and Azzah has brought her daughter. The little girl, four years old, speaks perfect English.

Muminah seems more relaxed. Hair escapes from her hijab. She leans forward, smiling.

“We like, now,” she said, mimicking, hand to mouth. “We eat.”

“We like to eat blueberries,” the little girl prompts, precisely.

“Blueberry crumble,” Muminah will say, tonight, with pride, handing a plate to her husband.

…

I stand in the doorway, watching the car vanish over the brow of the hill.

I think of how the Syrians must long to belong. Of how I feel the balm of happiness every time I feel at home here. And how it is the confluence of people and land that makes us who we are. Blueberry picking binds me and Muminah to the August day ; tides on the bay send the swift, shadowing clouds that cool our cheeks and the sun’s southern slide thickens the cricket’s song. If I were in Syria, she would teach me how to cook lamb with garlic and dried mint. She would teach me to grind cardamom. She would show me where to find pennyroyal and wild onions.

I turn back into my kitchen, where I’m making tomato sauce. As I chop and slice, I ponder how, in the midst of Syria’s civil war, birds hatch eggs, mint spreads, gazelles give birth ; and how it is all that we call wild, natural, the non-human to which we need to pay attention ; how, bearing the scars of ignorance, with humility and respect, we need to take our place amidst the other creatures on planet earth, who neither make war nor seek primacy. This is how we immigrants and newcomers and refugees have found our place in community : earning acceptance by yielding to what is given, gaining wisdom by knowing what is greater, and grounding ourselves by learning traditions—tomatoes into sauce, blueberries into crumble—using only as much fruit as the earth can bear.

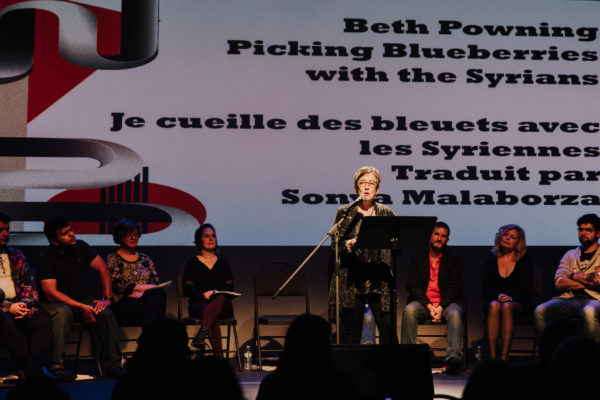

Beth Powning

Text published in No 17. Creating Community