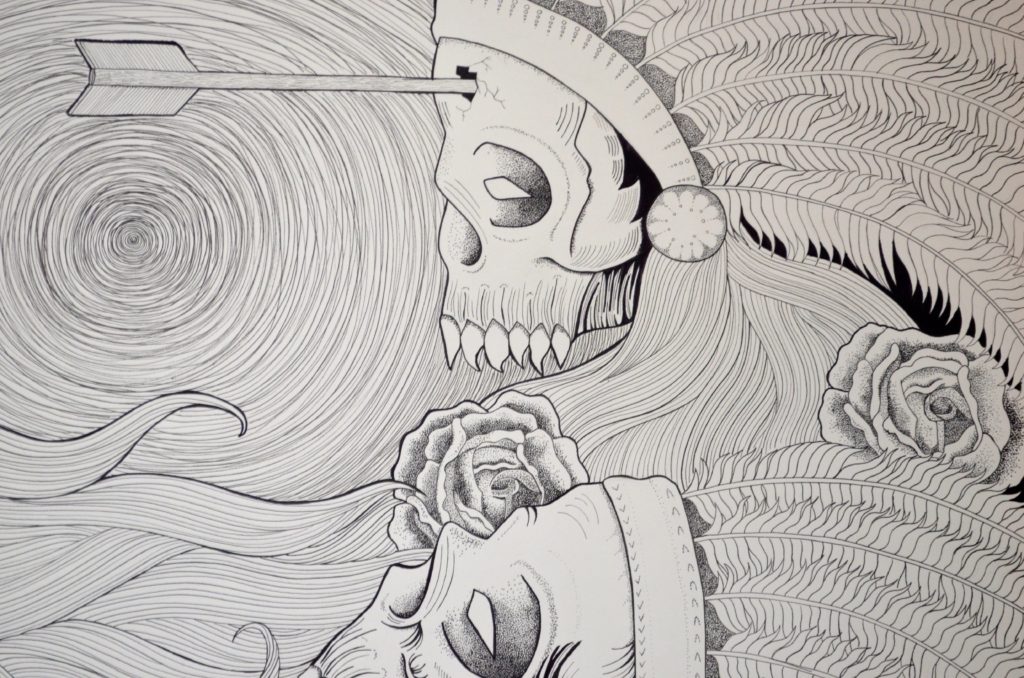

When the stranger was found near the village gates, he was barely alive. He wore the tattered remnants of armour, and wounds covered his thin body. “A soldier,” someone said. “But for what army ?” another asked. A hunched old man moved through the crowd, his staff held high.

“He is a soldier for the Army of Death,” he declared, sucking air between his teeth, and everyone stepped back.

The old man moved closer, peered down at the soldier. “We once waged war against them. We almost lost.”

When they turned the dying soldier over, they saw the black cross on his back. They didn’t remove the frightening mask of barbs.

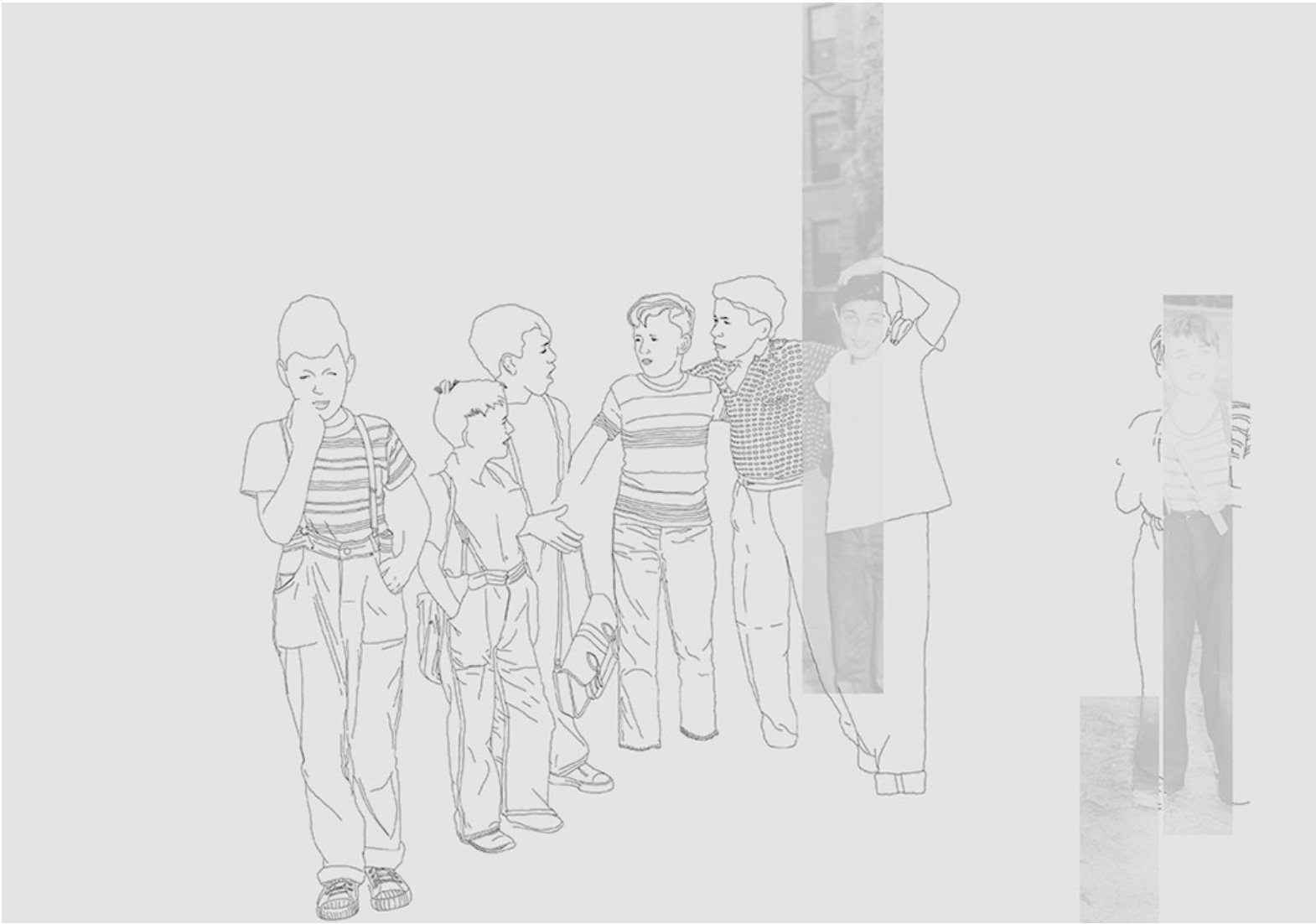

Who would let a stranger, let alone a soldier for the Army of Death, into their village ? They all looked to one another. It was beyond bad luck to do so ; who would invite such a stranger to your doorstep, to your dinner table ?

Let him die, yes ; let him die. He’ll be dead before sundown. He’s barely alive as it is. Should we bury him ? Burn him ? Should we let the birds take him away ? Should we let the winds scatter his dust ?

They liked the last, and left him there, to the birds, the winds, to become dust.

But early in the morning, three hours before sunrise, they heard a sound. At first, they couldn’t identify where the sound was coming from, though many suspected it was in their head and so tried to sleep longer, but sleep was no longer their country. The soldier for the Army of Death was at the gates, pounding. That was the sound. Over the gates, caught in the starlight, were the fast shadows of birds.

Nothing had ever penetrated the closed gates.

Nothing had a chance.

Throughout the morning the soldier pounded, a slow, rhythmic drum. He pounded while the people called out from their beds, We are a peaceful people. Let us alone.

Throughout the night, the soldier pounded.

“Long ago, we met them in the Lower Valley,” the hunched old man recalled. “Met them where the waters of the two rivers converge. The rivers were low that year, the vegetation dry, crumbling. There was one narrow bridge. The black-clad army wanted to cross towards us. We wanted to go their way.”

“Why ?”

“Our maps showed a lush land over the mountains. We would conquer it, feed our children.”

“And the dark army were protecting it ?”

“Yes, and they wanted us to starve. So we stormed the bridge, and when the bridge was full we threw off our armour and waded across the river. For the next day, until nightfall, our blood and their blood flowed into the river, turning it red.”

“That must have been a terrible sight !”

“Wherever the Army of Death goes,” said the hunched old man, “their black birds follow. They swooped at us, but we protected our eyes.”

He threw a branch into the fire, looked to those gathered ‘round. They listened to the pounding on the gate. “Our army was a thousand strong, theirs much smaller. By the next morning, we had one hundred men, and they ten. We were merciful, and we let them retreat to the mountains.”

By dawn the next day, the strange soldier sat at the base outside the village gate, head between his knees, gathering strength. His hammering had stopped when the sun came up, and the birds had flown off. A young woman slowly moved through the milling villagers, saw him through the slats in the gates. Watched him. She remembered a man one night, when as a child, she had secretly left the village, her adventurous spirit having driven her to explore. She had become lost. A masked man had come along the trail holding a fire high, and she had hidden in the thicket. He had paused, she remembered, had looked around, then knelt and placed objects on the trail.

A waterskin. A compass.

Was this the same man ? she wondered.

The young woman shouted and pointed, and all eyes turned away. She reached beneath her skirt and threw the full waterskin over the gates.

Later in the day, she threw fruit over the gates.

The hunched old man stirred in his bed that hot afternoon, his limbs trembling as he dreamed of the river battle with the Army of Death. He saw his brothers fall to the ground again and again, saw the black-clad army raise their swords and spears.

There was no lush land, sadly, only stones and dry streams.

Around him, the villagers, lacking sleep, moved aimlessly, told themselves the stranger wouldn’t make it much longer, he would die and all would be well again. The night was quiet. But when early morning came, it started, the slow, rhythmic pounding. “Let us alone,” they cried from their windows this time. “We are peaceful,” they lamented. They rattled pots and pans, something they knew would chase off evil.

But the pounding did not cease, and no one slept, and when the sun shone through the morning mist, the villagers started to gather. “Our plan just hasn’t worked, has it ?” a short man said. “He is only getting stronger.” “But he is a soldier for the Army of Death,” someone interjected, “he probably can’t die.” “He probably can’t feel pain, either,” someone else shouted.

They thought for a moment.

They were, however, a kind and peaceful people, and so for the next three nights, till sunrise, they listened to the pounding. Some decided to sleep during the day, to stay awake and count the stars at night. Others tried to talk to the soldier, to reason with him, shouting through the gate, “What do you want ? Why do you bother us ?”

But he would not speak.

“No one,” the old man told them from his bed, “no one has heard these strangers talk. Even on the battlefield, they made no sound, they simply pounded their shields and drums and fell silently.”

“They are not like us.”

“No, they are not like us at all.”

The young woman tried as well. Whispering, when no one could hear, “Do you remember me ? You saved me on the trail. I know it was you.” The soldier stood up, she saw. He tapped the gate from the other side, softly, but his thorny mask and dark eyes made her body tremble like the old man’s, and she could not listen for long.

“What are you ? What do you want ?” she asked.

She threw more fruit over the gate that day, just before dusk.

“Why won’t you talk to me ?”

The next day she threw no water or food.

The hunched old man, a strong warrior in his day, died in his sleep.

No villager had ever been interred within the gates. For centuries, burials had been held high up on the mountain, all the deceased belongings burned in a pyre. The villagers debated : Should we wait until the stranger dies ? Should we risk a plague and dig a deep hole in the village ? Can birds carry the old man’s body to heaven ? No one wanted to suggest opening the gates, facing the soldier who they’d left to die, who pounded so insistently each night.

The young woman stepped forward, hesitated, retreated into the crowd.

Just as the villagers had become accustomed to the pounding, it ceased. It had begun on time, three hours before sunrise. But a few beats into the drumming they heard a cry. Likely it was only birds squawking and screeching. They lay still in their beds, haunted by this silence, now unable to sleep in the drumming’s absence.

Slowly, as light crept over the village, they made their way to the gates, which stood undisturbed. “He is dead,” the first to reach the gates declared. “The solider for the Army of Death is no more.” There was no cheer, though some let out a long-held breath.

Others came through the crowd, carrying the old man on his bier. The mayor, still in his nighclothes, unlocked the gates.

Was he the last of his kind ? the young woman wondered. She searched through the stranger’s things, birds scattering while two large men rolled his lifeless body, armour and all, into a white cloth. They did not remove his mask.

His nearby pack, she found, held the waterskin, a small book, and little else.

A silver ring. A pair of mittens. A flute.

The book contained hand-drawn maps and pages and pages of scribbles. A diary, she concluded. She flipped through the pages. It was all so strange, and on the last page was a shaky sketch of the closed gates and pounding fists.

She slipped the diary into his burial shroud when the two large men walked by. They were moving up the mountain with their burden, no chance of catching up to the old man in his bier, but hoping to use the remnants of his fire.

Lee Thompson

Published in No 17. Creating Community