I am part of a community.

I don’t mean a village defined by boundaries, garbage collection schedules, and municipal taxation. I’m talking about townships of the heart, boroughs of the soul, and cities of the mind.

My community consists of writers, artists, musicians, photographers, and actors. It also includes readers and audience members. Editors, critics, and media, too, are family – uncles and aunts who stop by to offer opinions about our lives.

My parents weren’t literary. My father, a mechanic, read Western novels. My mother bore children as if she were a handmaid. That was only one of her jobs. In that community, such lives were expected.

My brothers and sisters, however, are writers.

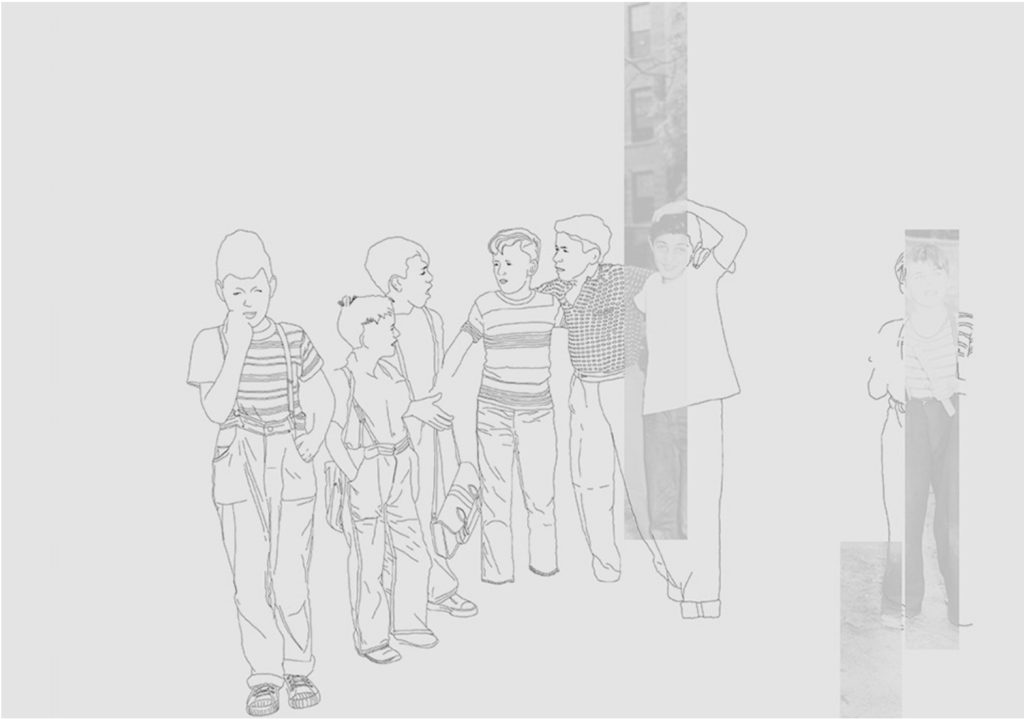

None of my childhood friends aspired to use words beyond their perfunctory functions. The only writers I knew were Louis L’Amour, Zane Grey, and whoever else’s book my father left open on the bathroom floor.

Teachers would ask what I wanted to be when I grew up, as if that were my only choice. I never said, “I want to be a writer.” I already was one, who colored outside the lines and read with the appetite of a starving tiger, as if each book that fell into my grasp were a captured lamb.

Long since grown up and moved away, I have seen my hometown only twice in the past thirty years. My community never was defined by borders.

I’m a Newfoundlander, and yet a citizen of the world. I’ve lived in British Columbia, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and now New Brunswick, where I feel I’ve settled, more or less. I travel internationally by hosting retreats, which feed my insatiable wanderlust.

In each place, I have found much to love – mountains, glaciers, beaches, and people. In the Fraser Valley, I lived among wiccans and pagans, though I never quite fit in, since I wouldn’t cast a spell to save my soul ; nor could I persuade myself to dance naked in the moonlit forest.

In Ontario, I found the arts, but not many artists. Most creative types worked at a college or cubicle. In Nova Scotia, I dwelt among career suburbanites dedicated to the pension they might someday receive if they worked hard and outlived their company.

Once published, I found, as they say, a sort of “tribe.” Still, I’m uncomfortable using that phrase both because it’s an appropriation of a colonial error and because it’s inaccurate : I don’t belong to a tribe. If anything, I might be a society of one, although no man is a society any more than he is an island.

But he can live in a cottage by a lake in the woods, far from the closest border-line community. He can come from away and stay at a distance to observe the villagers as they enjoy their lives, endure their trials, farm their fields, and raise their children.

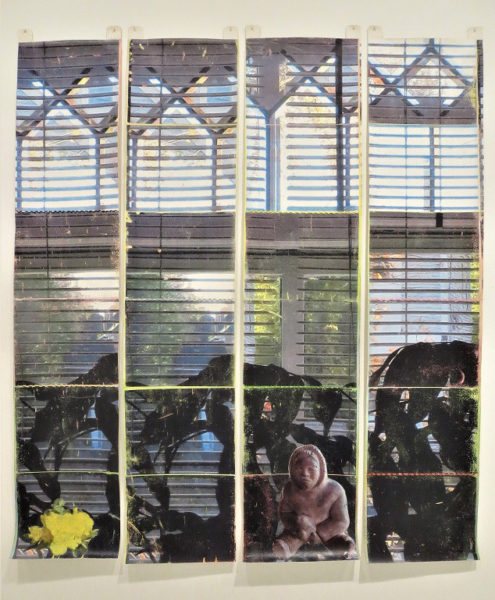

Most days, I work at my window that overlooks the lake. A blue heron summers here, where a pair of ducks and geese nest each spring. My first visitor, though, was a sheep, and after that came a little black cat. My disappointment with their domestic quality might symbolize my desire to sever ties with civilization.

Four years ago, my marriage disintegrated. Just when I’d found critical success, stood upon the apex of a frenzied creative outpouring and gazed up at the stars forever beyond my reach, I fell to the earth.

Exiled from and by myself, I launched towards Nova Scotia where I lived in a cottage at the edge of the ocean, where I wrote every day at Kate’s coffee shop among people with no idea of who I was. I often spoke to the curious launderette, the friendly waitress on a break from school, and the greasy mechanic who was nothing like my father. To them, I was a writer from Newfoundland who, clearly, would not stay.

Employment brought me to uptown Saint John, which teemed with people. Within weeks, I planned my escape to the countryside, to the woodland cottage by a lake where I now reside. Down a long dark road, at the end of a pitch-black lane, I live and teach by distance.

Meanwhile, the blue heron brought a friend this year. The geese prepare their children for the long flight southward. The trees shift – verdant green to bronze and scarlet. Several days ago, a red fox padded onto my front step, sniffed at my footprints, then crept away. Last winter, I watched a deer cross the frozen lake, then disappear into the roadside thicket. Curiously, these last two travelled alone.

The people of Sussex have been here for decades. They go to the same church and have kids in school together. They go to each other’s houses for supper. The mere thought of such camaraderie warms my heart, stirs my soul. I wonder, then : do I write only for an island of one ?

When I tell other writers where I live, they say, “You have the perfect writer’s life.” Some call it my own “little Walden,” but I am not some pale reincarnation of Thoreau. As with the animals, instinct compels me to nest and find comfort. Everything unrelated to writing has fallen away. This obsession satisfies my soul and is the only thing that explains my existence.

Alone time is necessary for composition, even self-composure. Community resides in my heart and brain – solitude lives in my soul.

Sometimes, though, I yearn for the company of others, the formation of deep, substantial friendship. I find myself on social media, yet careful not to lose myself there. I skim the surface, nibble the edges. The sound of one keyboard clicking in the forest of the night. I don’t count likes. I often forget to respond to comments. A creative outlet unlike any other, Facebook is my public time capsule. Hide-and-seek. I’m there, and yet not. I never surrender my solitude to that insatiable beast. Writers and readers gather and converse as if at a coffee shop where anything goes. Others lurk, but never speak to me. Former friends. Now Facebook friends. One warm, bright light who died last year, her page a living monument.

Despite isolationist tendencies, I have immense love in my life – personally and professionally. Besides a loving partner, I belong to a literary committee. I mentor, host retreats, and find intelligent conversation. But at the moment of connection, there is also disconnection.

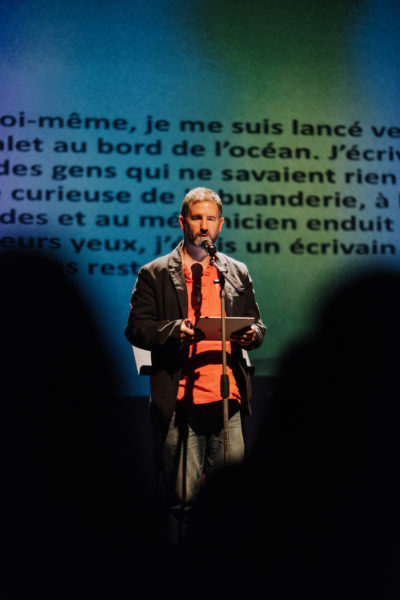

One recent November night, I hosted an open mic event filled with convivial, warm, literate people. At the end of the evening, I was transcendent. Perhaps, despite myself, I belonged.

Then the lights went out, and everyone went home. There are some to whom I didn’t speak, who didn’t speak to me. I wondered if they, too, feared the connection – whether that flicker in their eyes was for something burning in an otherwise dark night, that yet kept them distant and longing.

I often wonder how people can connect with each other, be certain that the people with whom they’ve surrounded themselves truly care, want to be there, and will always be there.

I have learned there is no always. People change. Communities shift in size and norms. We tolerate, in time, that which we once abhorred, and vice versa. Such is life.

My sense of a community is this : don’t underestimate their capacity for forgiveness. Don’t assume no one notices or that no one cares. Conversely, of course, don’t assume that anyone cares. By word or deed, they can drag you down. And yet a community can raise you up, hold you aloft, sing your praises, sustain your life from close nearby or from afar.

When I left Newfoundland four years ago, I had many friends and acquaintances – a communication that since has dried up like a once-thriving marshland. My community, still, has grown and improved, found authenticity in the wilds of New Brunswick. While my identity is as author, I am more. If I stop writing tomorrow, I am still someone.

A year ago, I suffered a concussion and, for several months, lost my ability to write. As is my nature, I kept to myself. And lo, here comes the community : near strangers, Facebook friends, offered to come and cook for me. A neighbouring single mother and her two children came to my place after a snowstorm and shoveled me out. Many people sent healing wishes by email, and I felt cared about.

There was no distance, no separation. When they perceived I needed them, they were there. Maybe that’s what community is all about – knowing not that you belong, but that you are loved for who you are.

Community is family. It isn’t just tolerant, but embracing. It’s an attempt to understand the incomprehensible. It is shining a lamp in the darkness, or turning on your iPhone to see the messages from people just checking in to make sure your light is still on.

Gerard Collins

Published in No 17. Creating Community