français / Mi’kmaq

– Translated by Jonathan Kaplansky

It is difficult for me to describe the emotion I feel when I have to speak about my country. I don’t know how to properly tell you about the nostalgia that runs through me. Long years have past since I left the land of my birth with tears in my eyes and sadness in my heart. I still remember it as if it were yesterday. I had to be separated from my father. Yon moun ke mwen respekte anpil. A man for whom I had a great deal of respect. A hard worker, yon nòm vayan, my hero. Yon ané pat sufi’m. One year was not enough. The little girl that I was did not have time to heal the wounds inflicted by the losses of the past. With time, I had to get to know a father who was nevertheless not a stranger to me.

My country evokes in me sadness, lack, sorrow, a failed and difficult childhood. Parties where I felt left out, friends I never had, men I never met. Mwen te senti’m lèd, e mwen te lèd paske mwen te genyen anpil amertim, kòlè, ak haine nan kè’m. I felt ugly and I was ugly with bitterness, anger, and hatred. The little girl that I was knew only that. Yet she is nostalgic for the land she did not choose, for a childhood she would liked to have experienced otherwise, for a past that she wishes could have been different. Mwen te vle viv tankou lavi yon ti lajenès, I would have liked to experience moments of joy. Mwen te vle viv de seri de plezi, I would like to have better memories. Mwen te vle viv yon jenès ke mwen ta ka raconter, I would have liked to experience a youth I could have enjoyed describing sans mwen pa kriye, without crying, sans mwen pa kaba, mwen pa triste, Without sadness.

…

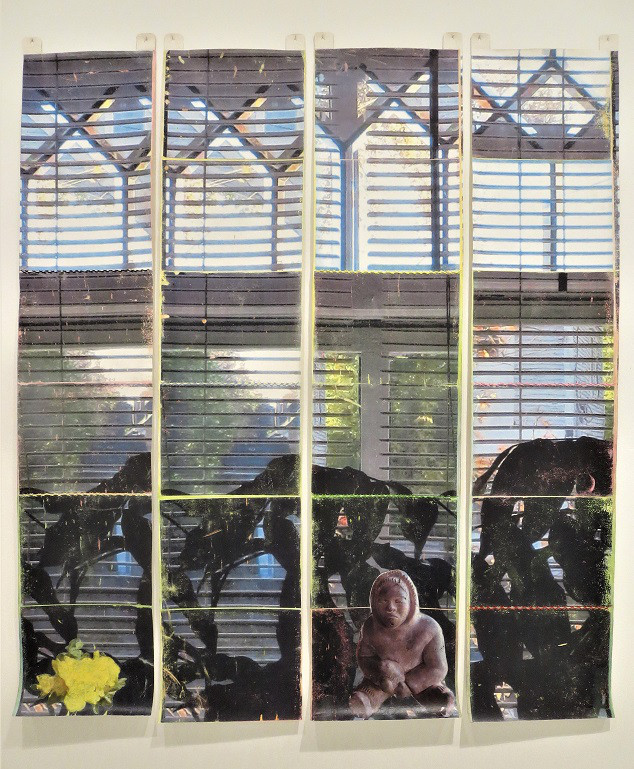

I was born on an island, a small country that was almost the laughing stock of every republic on the planet : Haiti : a cultural force overflowing with richness and diversity. A former colonial country derived from Africa, Amerindians and settlers, the country of my memories, my native land, offers an aerial journey with glimpses of our torn-apart, crippled society.

In the foreground, a mosaic of social classes stands out, where rich and poor cross paths and infringe upon one another on a daily basis. Pétion-ville/Jalouzi : an open-skied mariaj with residential areas and slums. In the background, there are puppets at the national palace, making this a society of spectators, teeth clenched, watching a drama unfold that is far from fictional.

The tradition of my native land is grounded in cultural and religious voodoo and the people are superstitious, spiritual, and animistic. Haiti, a country whose independence was achieved through hatred and blood, rebellion and disgust, wears a crown of thorns. Its cross is marked as in the time of Jesus Christ, guilty of being the “bloodthirsty queen.” The former pearl of the West Indies carries on its back the burden of liberating unfree spirits of long ago. Now a prisoner of the past combined with a shameful present, Haiti is proud, without being patriotic, of a history that it did not create, a history poorly learned, a history it experienced through the scars of its ancestors. The past repeats itself, and we have never managed to go beyond it and understand the revolutions and wars that should have transposed feudal Haiti into an enlightened Haiti in people’s minds and its superstructure.

Proudly flying high, my peau po’ w flag, my pretty little flag grows weary of being honoured with the song of the patriots. “For Haiti, our Ancestors’ country, we must walk hand in hand.” Learned at school, the hymn is mechanical, devoid of meaning for a young Haitian whose passion is elsewhere and whose future lies in a foreign land.

The angry flag, tired of enlivening poorly maintained streets, the markets at Croix-Bossales streaming with orphan children, beggars, and criminals, says it is fading its blue and red woven by Catherine Flon, back when people’s rage to free themselves from the chains and the Machiavellian master were at their height. Still, it thinks paradoxically, ke menm si ayisyen an pa resevwa kek bon baton nan deyè’l, li toujou rete esclav nan tèt li. The Haitian freed from the whips is enslaved by his land.

…

Immigrating.

Adapting to a foreign land is a challenge for a Haitian. Everything changes ; nothing is the same. The temperature drops, mentalities are different, and cultures are all distinct from one another. The Haitian therefore has to create a new skin to survive, a new understanding of her environment. She must be able to immerse herself in a world and come to grips with it.

During her period of adaptation, she will get to know the other, and herself. From that point on, she will be obliged to open herself up to the outside world. She will adjust to the new culture without losing herself, fitting in without asking for any changes in the natural and legitimate laws of the country. Through her experience, she will gain new values, and lose some as well. These new encounters will nourish her mind with recent ideas that are controversial to her native culture.

Her experience will allow her to build a bridge between herself and herself in constant evolution. This new citizen of the world, from that point on, will become aware of a new reality, of a global vision. From this change in mentality, her day-to-day life will arise.

…

From refusals to experiencing failure, from unemployment to food shortages, from one small job to another, from call centres to the boldest small projects, with no guarantee of financial stability, the young immigrant, intelligent and ambitious, with a BA in hand and skills, is far from the American dream.

The working world is fierce, filled with pitfalls. For this reason, it is easier to survive than to live. The immigrant, throughout her career, will likely aim for success in her chosen field. A success that, by default, will be defined by the other, or by others.

The immigrant is worried about papers. An immigration form, which will grant her the right to remain on foreign soil. She will have three years, so three chances to obtain it. Although important, this form is obtained at the price of a suitable job, a decent job, a job often unworthy of her. With two similar CVs, the native wins. And so the foreigner is obliged to do double the work to be valued for it. She will, to begin, invest thousands of dollars in a privileged education. A privilege that, afterwards, will perhaps not weigh heavily in the balance of the job market that is sometimes discriminatory, sometimes closed.

No assistance is provided to international students, no grant. Education is a privilege for the foreigner. You have to earn it from the sweat of your brow, $6,000 a semester. If Mother and Father don’t have the money, you make adjustments. After all, didn’t you sign a contract with Immigration ? No money, no life, no papers, no life. You become master of your destiny : succeeding or failing depends on the number of hours spent at work, the ability to deal with the stress of lack of funding. You have to register for the next semester, have to live, have to eat. You are alone, far from family, completely at a loss, on your own. Solitude is cruel and the problems enormous. The examples you see before you are not the best : students, graduates, sometimes with a Masters degree, fill the call centres. Reality encourages you to drop out. You’ll have children, get married, leave school and be condemned to call centres, irrevocably. You make do with successfully completing courses, of course, to obtain a “nothing” degree. You will send out tons of CVs, go to tons of interviews ; out of a thousand applications, you have a grain of hope. Not enough experience ; the quota has not yet been reached. Don’t give up ; you must persevere, especially when you are a woman and you are black ; you’ve got a long road in front of you. The ideal world does not exist : you have to fight.

While admitting that my conclusion is illogical and my equation unbalanced, I would say that the immigrant is liable to repeat, even if she is educated, the typical pattern of the foreigner. Some get by, but the journey is long, the road difficult. I salute all those who have fought, who are fighting, and are still fighting to not repeat the errors of their elders.

Personally, I see myself as among those who have succeeded, who stand out. I want to be someone who brings her stone to the building of the adopted society, offering my gifts and my cultural baggage. I want to work with people who can offer me solid and worthwhile experiences in this foreign land. I like arts and culture. Above all, I want to learn, share, and observe.

Sheedy Petit Jean

Published in No 17. Creating Community